The Return of Planet Drum

“In the Groove”

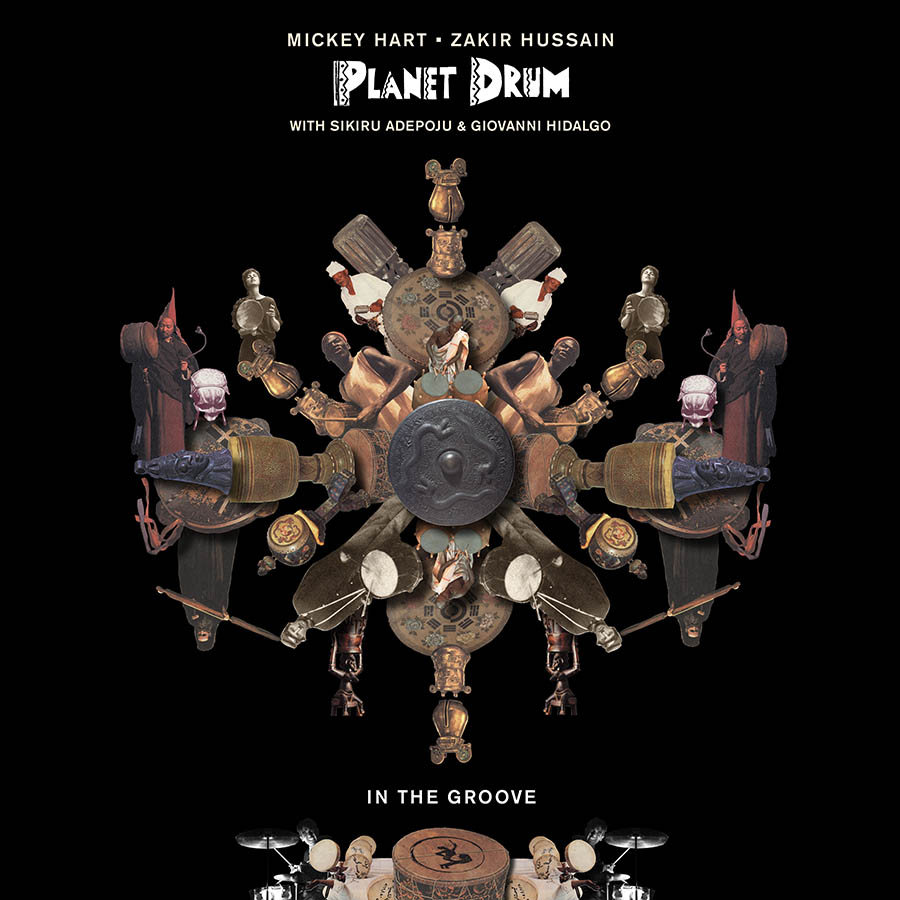

IN THE GROOVE – OUT NOW at https://fanlink.to/planet-drum.

SHOP VINYL & FIND A RECORD STORE NEAR YOU: https://recordstoreday.com/UPC/819376043739

Rhythm and percussion form the universal pass key to the world’s music, the underlying connection that can unite an American rock and roll drummer who started in the marching band world with the master of Indian tabla, the “Mozart of the Nigerian talking drum,” and one of the great conqueros (conga players) alive. Mickey Hart, Zakir Hussain, Sikiru Adepoju, and Giovanni Hidalgo are Planet Drum. The origins of Planet Drum lie in Mickey Hart’s 1968 encounter with the great Indian tabla player Allarakha, best-known as Ravi Shankar’s accompanist. Already a member of the Grateful Dead, Hart had by all measures achieved considerable success, but his passion for studying other rhythmic worlds was just taking off. His work with Allarakha introduced unusual time signatures into the Dead’s repertoire; then the master gave Mickey his greatest gift by introducing Mickey to his future life partner in rhythm, Allarakha’s son, Zakir Hussain.

In the 1970s they collaborated on the Diga Rhythm Band, which was largely composed of students from the Ali Akbar Khan School of Music, where Zakir taught. Their album Diga was put out by the Dead’s Round Records in 1976 (and re-released by Rykodisc in 1988), and is a landmark in American percussion music. As the ‘80s passed, Hart buttressed his experiential studies with anthropological ones, starting with Joseph Campbell and moving through academic studies of the shamanic origins of percussion. An enormous timeline of 3” by 5” cards nicknamed “the Anaconda” encircled his studio, and the first results were the books Drumming at the Edge of Magic, a memoir and manifesto, and then Planet Drum, a history and study of percussion and its applications.

The latter came accompanied by a recording of the same name, and it was extraordinary. Hart and Hussain gathered some of the greatest drummers alive, from the great Nigerian Babatunde Olatunji, Brazilian master Airto Moreira and vocalist Flora Purim, Sikiru Adepoju, and South Indian ghatam master T.H. “Vikku” Vinayakram. The album would earn the first-ever Grammy for World Music after spending 26 weeks at #1 on the Billboard charts, then sparked a triumphant nation-wide tour. A second Planet Drum tour was succeeded by the equally successful Global Drum Project.

In the years to come, Hart’s interests covered multiple musical projects, including a collaboration with Dead lyricist Robert Hunter called Mystery Box, another with the members of Planet Drum called Supralingua, and a more rock-oriented Mickey Hart Band. Having seen the healing value of percussion, both via shamanic tradition and modern drum circles, he joined the board of the Institute for Music and Neurologic Function where he worked with Dr. Oliver Sacks. Later, he would work closely with U.C. San Francisco neurological scientist Adam Gazzaley studying rhythm and brain wave function. Then he voyaged totally beyond Planet Earth to compose “Rhythms of the Universe,” working with astrophysicist and Nobel Laureate George Smoot to transform radiation/light waves from the cosmos into sound. In between, he filled out his time with a variety of post-Garcia Grateful Dead projects and remains a member of Dead and Company.

Planet Drum remained on his mind, though the combined travel schedules of the four of them made coming together to record and tour very difficult indeed. The pandemic began to close concert halls around the world, and Mickey gulped. “’What am I going to do? I’m going to go nuts.’” He asked himself, “What makes me happy? Of course, it’s always something to do with rhythm. In this case I went to the source, to Planet Drum, a state of mind where rhythm is king. I made sure to have a solid dose of rhythm every freakin’ day. I worked with a second engineer on the weekends – I could hardly let a day go by that I didn’t bathe in the sound; it was my sanity… it was my everything.”

Covid had also presented a gift to artists: time enough to create. Zakir in particular wasn’t, as Mickey put it, “flying across the universe.” “When people are in trouble,” Mickey continued, “when they’re threatened, they go to the things that really matter. We were going to the mountain, the very sweet spot of my world. I also thought there was a great need for this. Our world is out of rhythm, our culture has lost its groove. Rhythmic unity among cultures is what Planet Drum is about, and with the world in torment, it sends a powerful message of healing.” In Sikiru’s words, “Music

speaks one language.”

Having played together pre-pandemic, their work became one of editing and spatial processing, what Hart called “a supreme effort at tuned percussion.” Zakir added, “The digital processing allowed us to tune the instruments so that tabla, for instance, could become a melodic, arpeggiated instrument. The congas became a choir which harmonically supported the musical structure. And of course, Sikiru and Giovanni—you don’t tell masters what to play. We’d give them an outline and say ‘Make it smile,’ and they would. The filigree work was put in by all four of us.” By the end, Mickey’s genius gift for breaking deadlines, also known as “it’s not done until it’s done,” allowed them to come together face to face at the conclusion of the process and play live together. As Zakir put it, “The original energy of Planet Drum that was there with all of us playing live was somewhat recreated, which added human warmth to the tracks.”

“Jazz with a backbeat,” Mickey remarked. “It’s a dance album. It was always on my mind to do something with Zakir that made people dance, as opposed to just listen. But I thought it was time to dance, for Planet Drum to dance. This is celebratory. It has a spatial quality that none of the others have, and it has a backbeat, which makes you dance. I wanted to make a record for people to enjoy and come out of the viral load world of the last two years…this is a trance dance band. I kind of combined everything in this one—thanks to the updates of technology, we could work with space as well as the groove.”

“It’s a groove album,” said Zakir. “Very little virtuoso soloing, but four of us in sync within the groove adds up to something incredible. It’s a real challenge to do just enough in support of the groove, adding exclamation points, but never disturbing the groove atmosphere. It’s a feel-good, jump up and down, tap-your-toes dance album. It also has a combined organic and electronic sonic experience that’s very warm.” One reason for the warmth was their group response to catastrophe, namely a raging case of diabetes that began to steal Giovanni’s fingers with amputations. The greatest conguero of his generation confronted the loss of his musical world and overcame pain and disability to reinvent his playing, creating a new stick and hand technique for the conga.

Three voices dot the album. Two are the voices of brilliant young singer/drummers from Benin, West Africa, named Melissa and Ophelia Hie. They lived in Paris, and since Zakir had a show in Berlin, he popped over to France on the way home and spent two days in the studio with them. “They gave a lot to the album,” he remarked.

Finally, Planet Drum’s ‘father’ was the late, great, Babatunde Olatunji, who passed away some years back. “Baba,” as he was called, is the word in India for father, grandfather, and wise sage. Zakir thought he was all those things, a human being but with “ocean like depth of knowledge and smarts.” His voice, which Mickey recorded in 1995 for the Mystery Box sessions, gives In the Groove a benediction and a blessing. Planet Drum rolls on.